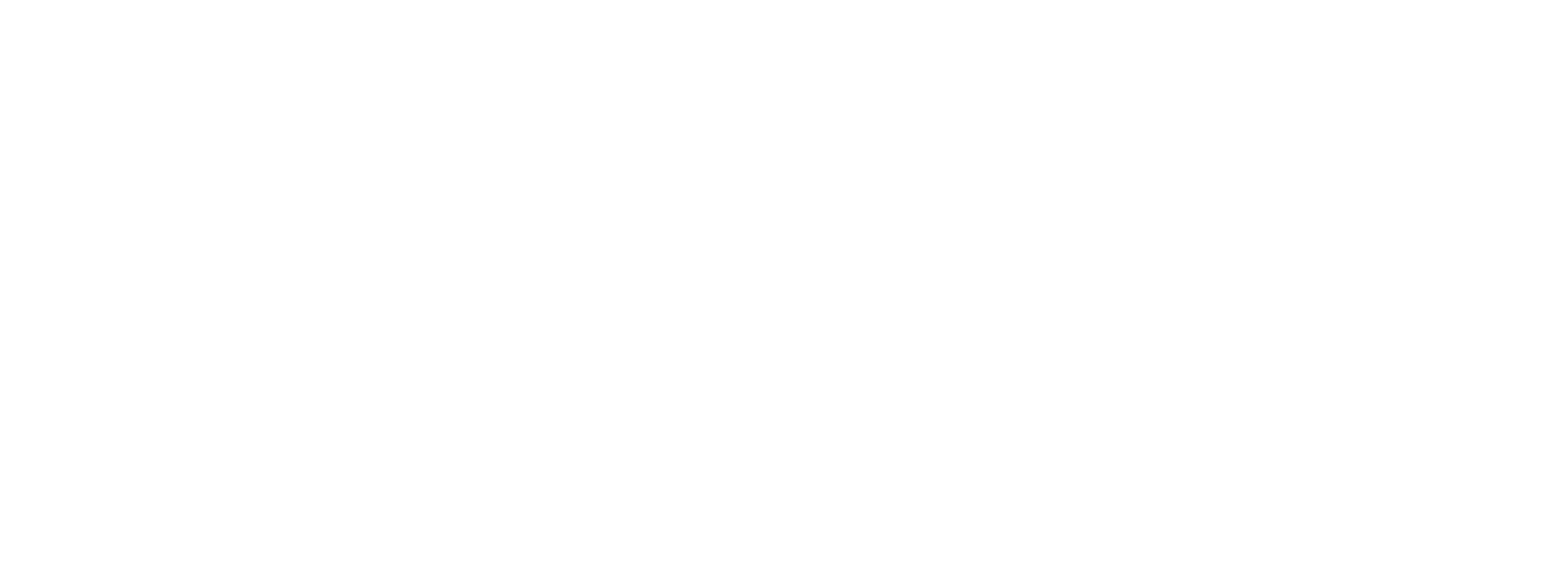

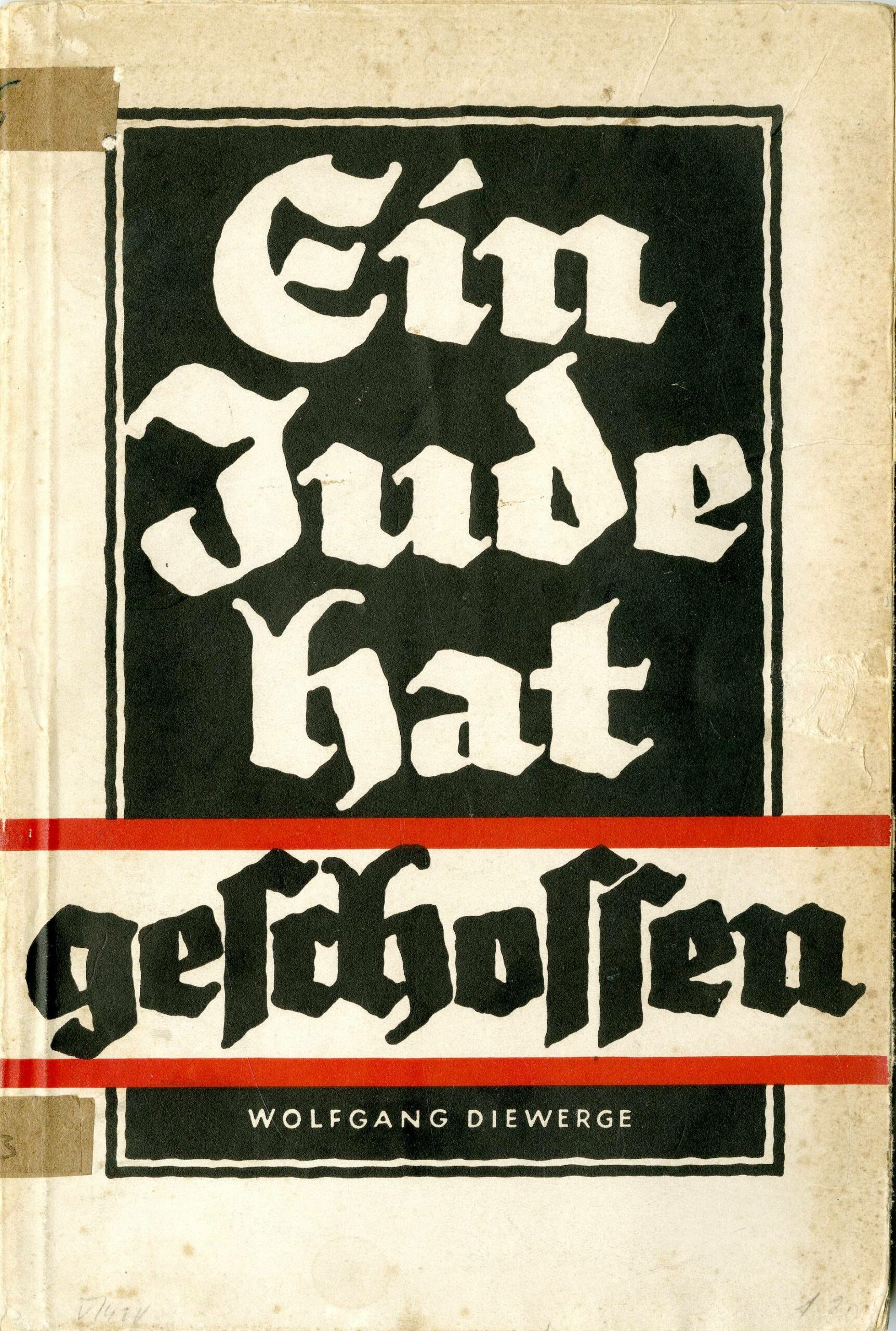

The yellow patch is the shape of a Star of David made of yellow fabric, known as an identification mark and a stigma for Jews in the occupied countries during World War II. According to the regulations of the German Reich from 1938, every Jew in the German occupation territory must wear a yellow patch. It was determined that the patch would be at least ten centimeters in size, in the shape of a Star of David with the inscription jude inside it (see below). In the center of the Star of David was printed the word "Jew", in the language of the country where the Jews were forced to wear the patch. The writing was usually in a font that seemed to be borrowed from ancient books, in order to create feelings of rejection towards the Jews by the various peoples in the occupied countries. For example, in German-speaking countries the word Jude was printed in the Netherlands, the word Jood was printed in France Juif and so on. There were countries where only the letter J appeared on the patch, such as Belgium, and countries where no letter appeared on the Star of David, such as certain places in France and Germany, Hungary, Romania, Slovakia, and Tunisia (see below). There were countries where the Jews were forced to wear pins with a local letter that marked the word Jew or "button patch" such as in Bulgaria.

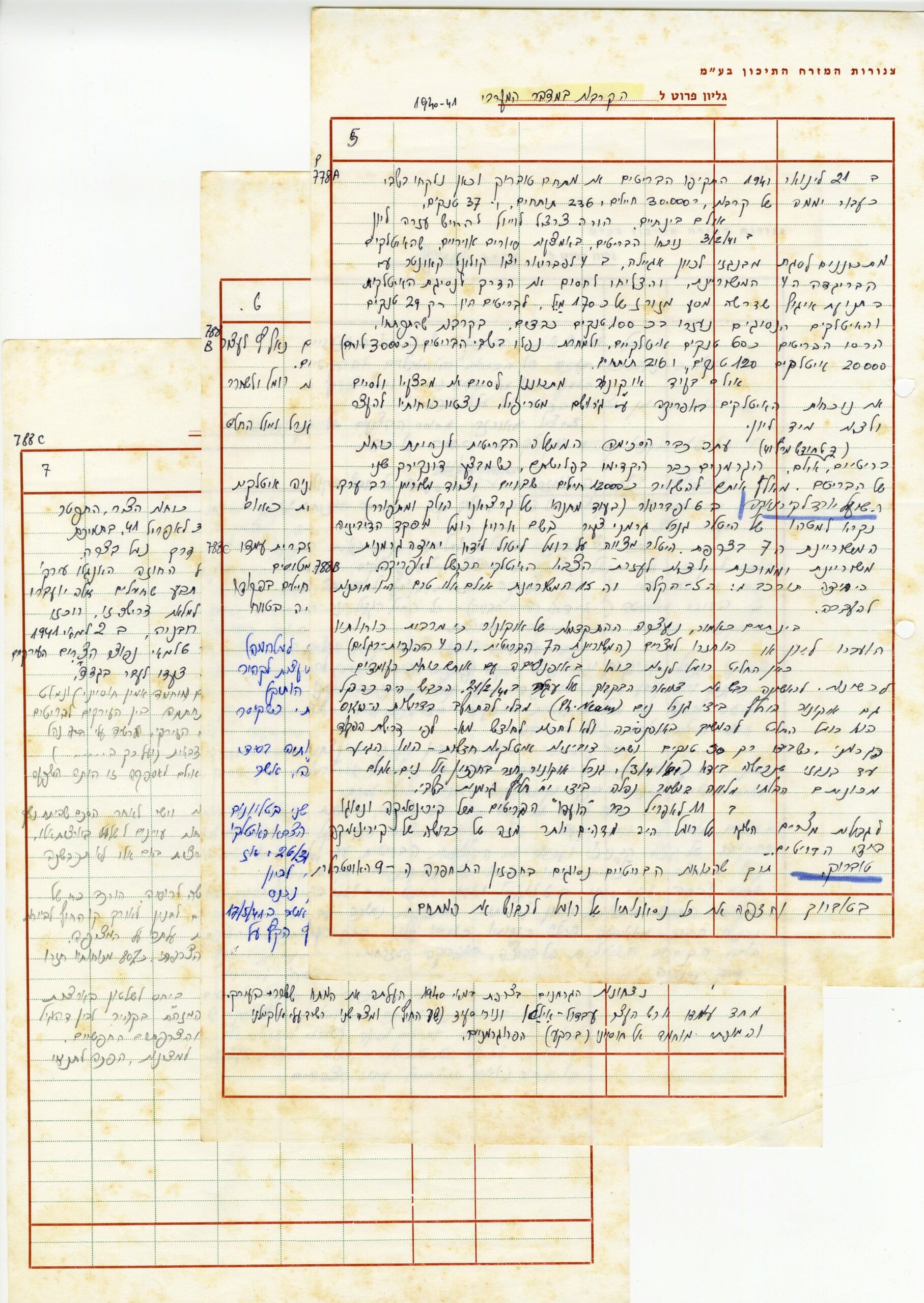

The idea of marking Jews with a different color on their clothes already appears in a collection of Islamic laws known as the "Contract of Omar", attributed to one of the early Muslim caliphs Omar bin Al-Khattab (7th century), over the generations there have been many forms of marking the Jews by clothing Special in the countries of Islam and Christianity, such as the Jews hat or carrying a symbol on their clothes. Similar to the yellow patch as a sign of disgrace during the Holocaust, in some European countries the Jews wore a "white ribbon" on the arm with a blue or black Star of David. The proposal to renew the decree of disgrace during World War II was first brought up by the Nazi war criminal Reinhard Heydrich in the debate that took place following the Kristallnacht riots in November 1938. Heydrich was among the main responsible and initiators of the extermination of the Jews and the "Final Solution" plan. According to the instruction, the patch is worn on the garment on the left side of the chest, or on the right arm under the armpit. Jews who forgot the sign when they went out on the street, or whose sign did not match the instructions, were officially liable to fines and imprisonment. At the entrances of the houses in Warsaw there were warnings not to forget the film. In a message from the Judenrat in Bialystok dated July 26, 1941, it was stated that "according to the authorities' warning, Jews who do not wear the yellow patch on their waistcoats and on their backs will be severely punished - up to death by shooting."

In his book "The Doll's House" De Noor described the process of the Jews' adaptation to wearing the patch: "At first, when the decree came out from the Germans that all Jews must wear the badge of Jewish disgrace on their left arm, it hurt... At first many avoided going out into the street, because They will be seen with the mark of disgrace on their arm. After a short time this became a habit... Life in the ghetto again behaved as usual, and no one paid attention, did not even remember, that the mark of disgrace was wrapped on his left sleeve. Rather: parents took care of their children and children of their parents , before going out into the street, lest they forget, God forbid, to wear the badge of shame. In orderly houses, the inscription hung above the lock of the door facing the street: 'Didn't you forget the badge of shame?!' It was a kind of new mezuzah... In families where cleanliness was still strictly adhered to, the mother would wash with the remaining soap in her possession all the klon bands, so that the children would wear them on Shabbat... Brides in the ghetto presented their grooms with silk klon bands, which they embroidered on with silk threads Blue the German word JUDE inside a Star of David... and that's how everyone got used to being marked. Then the new decree came out: 'The Jewish symbol will be sewn on the place of the heart!' At first this also hurt, but they immediately got used to it... Many people were comfortable with this change, since the Jewish emblem sewn into the garment relieves them of the constant worry that they might forget it and go out on the street unmarked." (K. Tsatnik, The Doll's House, 10, 4, p. 131)

The yellow patch is one of the clearest signs of the Holocaust of European Jews. There is almost no object that raises the memory of the Holocaust more than this disgrace. This is the reason why important institutions for the commemoration of the Holocaust, universities, and museums throughout the country and the world that deal with the commemoration of the Holocaust make great efforts to locate yellow patches of survivors, and present them in exhibitions to the general public in order to perpetuate the memory of the Holocaust for future generations. Over the years, the presence of yellow patches from the Second World War period is becoming more and more rare. This is for several reasons: a. The Jews who were put on the death trains and sent to the extermination camps - immediately upon arriving at the camps, their clothes were removed along with the yellow patch, and they were given prisoner uniforms with different markings according to their "prisoner" definition. B. Most of the survivors who managed to survive the inferno, immediately after the end of the war, the initial act of liberation they performed was to tear off the patch from their clothing and throw it away out of the liberating feeling of freedom. They did not have any logical reason to keep the patch, which caused them strong feelings of rejection throughout the years of the war. The writer Yehiel Di-Nor once described his difficult feelings the first time he went out into the streets of the ghetto with a yellow patch sewn to his clothes: "It seemed to me that all the houses, all the windows, from all sides, even the stones of the street were pointing at me and saying, ``The city is marked!'' The girl Eva Heyman She described in her diary on April 5, 1944, the day she had to wear the patch: Today Marishka (the family's helper) came to pick me up from the Hananis and sewed a star - a patch on my brown spring coat, tightly fastened just above my heart... On my way to Grandma Louisa, I met the stars , these people walked the street so mournfully, with bowed heads." In the testimonies of survivors recorded after the war, you can hear many times how they say: "As soon as the news of the end of the war came, I tore off the yellow patch and threw it away...". This was also the reason that as part of the reparations and reparations agreement that was paid to the Jews who were victims of the Nazis, the Germans at one point began to pay compensation for the fact that the Jews were required to wear identification patches on their clothes in the ghettos. However, there were survivors who kept the patch together with personal documents from the war period out of a sense of mission and responsibility towards their family members and future generations. Of course, the greater chance of finding yellow patches that have been preserved since the war is precisely from those countries where the regulation was sweeping, and the number of Jews who were required to wear the sign of shame was large, in cities where there was no blanket obligation to wear the yellow patch, and in light of the fact that, as mentioned above, many Jews preferred to get rid of it, it is has become even rarer. This is the case, for example, in Tunis.

The yellow patch of Tunisian Jews

Many Tunisian Jews were sent to forced labor camps. On November 9, 1942, German and Italian forces entered Tunisia in response to the Allied invasion of Algeria and Morocco. The German invasion was accelerated when the Americans landed in North Africa. The Germans acted quickly to overcome the American forces that had arrived in the area. The handling of Jewish affairs was transferred to the German-Italian command, headed by a German general. At the end of November 1942, the Germans took the first anti-Jewish step in the area by arresting four of the leaders of the community, among them Moshe Burjal, the president of the community. The dignitaries were released after a week following the intervention of other important people such as the mayor of Tunis and the Italian consul. It is likely that if the German army had remained in Tunisia, the situation of the Jews would have worsened. But this army, which consisted of a few weak soldiers, was an army in which a lack of Discipline and self-confidence, he was surrounded by the Allies from all directions without the possibility of retreat and invested all his strength in survival. On Friday, May 7, 1943, the Allies liberated Tunisia from the Germans. After six days, the campaign in Tunisia came to an end. In 1946 the Jewish community in the city The capital Tunis had a population of about 34,200.In 1945, the wave of immigration to the Land of Israel began, first as illegal immigration and after the establishment of the State of Israel, legal immigration within the agency and youth immigration.

In past sales of Dynasty, a yellow patch from Tunis was offered for sale twice, see here and also see here. One of the patches came from a Tunisian family that immigrated to Israel in the 1950s, whose father himself was employed in forced labor building fortifications in Tunisian cities. At the end of the war, he kept the patch for which he turned from a "symbol of disgrace" into a "symbol of victory" over the Nazis and the dictatorship, and so that future generations would know the tragedy their ancestors went through to remember and not forget.